|  Just

as Nasa is smashing 'a space probe the size of a washing machine into

an object the size of Manhattan' this morning the post arrives including

the latest issue of The Beany (see below) and a preview copy

of BBC Wildlife Magazine for August which includes some of my

sketches illustrating an article by Stephen Harris, professor

of biological sciences at Bristol, on animal tracks and lie-ups. Just

as Nasa is smashing 'a space probe the size of a washing machine into

an object the size of Manhattan' this morning the post arrives including

the latest issue of The Beany (see below) and a preview copy

of BBC Wildlife Magazine for August which includes some of my

sketches illustrating an article by Stephen Harris, professor

of biological sciences at Bristol, on animal tracks and lie-ups.

It's an honour to be in the magazine, even if seeing my work in the context

of stunning photographs and elegant wildlife art makes me feel as if I've

walked into a champagne reception in my old anorak.

'We all loved your work', Simon, the art editor reassures

me, 'so don’t throw that anorak away yet!'

This hare, in my preliminary roughs, didn't make it

into the magazine because the author wanted me to show just the tracks

and lie-ups rather than the animals themselves. Quite a challenge: my

job was to draw not the hare, not a botanical study

of grasses, but a concept, a pattern: the impression the animal

leaves as it rests or moves amongst the grasses.

Birds

Britannica Birds

Britannica

The August issue of BBC Wildlife also includes features on our

wild coasts (which makes me want to get out there again soon), some charming

photographs of water vole behaviour and a canoe safari along Scottish

canals. There's a preview of Mark Cocker's Birds

Britannica (shouldn't that be Avifauna Britannica?) while,

in his regular column, the book's co-author, Richard Mabey,

writes about the place cranes have in our dreams, myths

and imagination. He asks:

'What is it about cranes that has elicited this kind of response, across

the globe and throughout history?'

The Crane-bag

Mabey's

question gets me reaching for my battered copy of The White Goddess,

'a historical grammar of poetic myth' by Robert Graves

(1895 - 1985), which includes a chapter on Palamedes and

the Cranes. Mabey's

question gets me reaching for my battered copy of The White Goddess,

'a historical grammar of poetic myth' by Robert Graves

(1895 - 1985), which includes a chapter on Palamedes and

the Cranes.

Palamedes, 'the inventive one' in Greek mythology, was

credited with inventing writing after watching cranes. The V-shapes of

a row of cranes in flight resemble the earliest forms of writing, which

consisted of chevron marks impressed on clay tablets (those are Canada

geese above, but you get the idea). Another version that I've read somewhere

is that the shapes the cranes make in their elegant but awkward courtship

dance gave Palamedes his inspiration. In a similar myth, the Egyptians

credited Thoth, whose symbol was the white ibis, with

the invention of writing.

The Crane-bag - carried by Palamedes, Perseus or Hermes,

depending on which version of the myth you're reading - was made from

the skin of a crane, and contained . . . well, that's a bit of a mystery;

'the contents of the Crane-bag were a close secret and all reference to

it was discouraged,' says Graves, darkly. There's a powerful magic attached

to the alphabet.

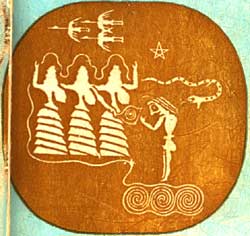

Graves

gives us some clues: Graves

gives us some clues:

'Imagine the pictures on a vase. First, a naked young man cautiously

approaching three shrouded women of whom the central one presents him

with an eye and a tooth; the other two point upwards to three cranes

flying in a V-formation from right to left. Next, the same young man,

wearing winged sandals and holding a sickle, stands pensively under

a willow tree. (Willows are sacred to the Goddess, and cranes breed

in willow groves.) Next, another group of three beautiful young women

sit side by side in a grove with the same young man standing before

them. Above them three cranes fly in the reverse direction. One presents

him with winged sandals, another with a bag, the third with a winged

helmet.'

It's hardly surprising that as a nature writer, Mabey, who also often

stands pensively under willow trees, feels a special affinity with cranes,

and they make an appearance - a symbol of hope and healing - in his recent

Nature Cure (which I read while in Norfolk, see 26th

May).

Graves thought that poetry wouldn't return to Britain until the cranes

danced again. Perhaps we won't have to wait too long.

The Beany #2

I

think of Michael Nobbs as the poet amongst drawing journallers,

even though his subject matter at first sight seems determinedly prosaic.

There's a cadence in his sequence of drawings of teapot, bottle, pen .

. . leaf . . . that reminds me of minimalist music. He weaves a wistful

skein of from the frayed and tangled threads of our everyday lives. I

think of Michael Nobbs as the poet amongst drawing journallers,

even though his subject matter at first sight seems determinedly prosaic.

There's a cadence in his sequence of drawings of teapot, bottle, pen .

. . leaf . . . that reminds me of minimalist music. He weaves a wistful

skein of from the frayed and tangled threads of our everyday lives.

Nobbs makes a trip to Ikea into a revelation - like a trip to Valhalla.

As so much of his work centres on beautifully designed still lives of

sauce-bottles and pickle jars, it's interesting that he reveals that his

father once worked as a butler.

'I've never been very good at giving things shape,' he writes, 'It's

much easier to drift and let things take a shape of their own'.

He's searches for insight into the deeper mysteries of life in the most

commonplace of objects and they do indeed take on a shape of their own;

they assume a symbolic, mythic dimension in the gentle intensity of his

drawings. For Nobbs, drawing probably is a matter of life and death:

'I think I'm slowly recovering my perspective,' he writes, and you feel

that he could mean either in his life or in his drawing.

Links

BBC Wildlife

Magazine

The Beany

Richard Bell, richard@willowisland.co.uk

|