|

Constable CloudsFriday, 25th April 2003, South Yorkshire |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Rocks | History |

Workshop |

Links | Home

Page

Rocks | History |

Workshop |

Links | Home

Page

![]()

Seen

from the Dearne Valley line the south Yorkshire countryside is coming

into Constable lushness. Hawthorns are already bright green, ashes are

still leafless but covered in blossom, birches are

Seen

from the Dearne Valley line the south Yorkshire countryside is coming

into Constable lushness. Hawthorns are already bright green, ashes are

still leafless but covered in blossom, birches are peppered with fresh leaves, willows with catkins, while sycamores and

horse chestnuts are well into leaf. A kestrel flies over a scrubby embankment

near Rotherham. Broom and gorse are in full bloom on an embankment by

Meadowhall.

peppered with fresh leaves, willows with catkins, while sycamores and

horse chestnuts are well into leaf. A kestrel flies over a scrubby embankment

near Rotherham. Broom and gorse are in full bloom on an embankment by

Meadowhall.

I arrive at the Millenium Galleries, Sheffield, before they open so there's time to sit in the Winter Gardens and sketch this bird of paradise plant. The tall flower stems grow up from a rosette of large glossy leaves, the whole thing reaching about 4 feet high.

On Brighton Beach

When

Constable (1776-1837) visited Brighton he invariably

turned his back on the fashionable resort and headed for the beach. In

those days it was a place of work with small colliers beaching themselves

(deliberately) as the tide ebbed to off-load coal. The Chain Pier,

Brighton, (left, © Tate Gallery) the subject of one

of Constable's major paintings, was constructed not as a promenade for

holidaymakers, like the Victorian seaside piers, but to enable colliers

to unload.

When

Constable (1776-1837) visited Brighton he invariably

turned his back on the fashionable resort and headed for the beach. In

those days it was a place of work with small colliers beaching themselves

(deliberately) as the tide ebbed to off-load coal. The Chain Pier,

Brighton, (left, © Tate Gallery) the subject of one

of Constable's major paintings, was constructed not as a promenade for

holidaymakers, like the Victorian seaside piers, but to enable colliers

to unload.

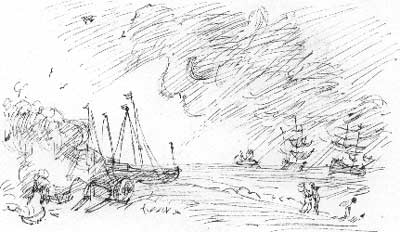

My pencil sketch (below) is from a small (a bit bigger than postcard size) pen and ink and wash sketch by Constable, Coast scene with Colliers on the Beach at Brighton, made in 1828 and on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum for this exhibition of the artist's work, A breath of fresh air, now coming to and end at the Millenium Galleries. At first glance I assumed the boat was larger, perhaps because of the dominant position it holds in the composition, but when I started sketching I realised that it's a small vessel. It appears to me that two men are leaning with their backs against the hull, perhaps to take sacks of coal. The figure on the right might be stooping to pick up any spilt coal as the tide comes in (or is it going out?).

I'm impressed by the confident lines of mast and rigging, and the suggestion of the foreshortened curve of the hull, something I find very difficult to draw convincingly on the rare occasions when I've drawn boats. I'm sure this must have been drawn on location, probably with the threat of rain to judge by the squall out to sea and I know how hard it is to be relaxed in your work amongst such chaos. I didn't notice any rain spots on the drawing, so perhaps Constable was lucky this time.

The masts of the ship on the far left by contrast are drawn with a fair amount of wobble in the lines. I guess that, as the foreground boat is so precisely drawn, that this is to give a kind of atmospheric perspective simply through the use of line.

The boats out to sea are no more little crescents but their position makes you aware of the power in that squall. I'm amused that the most distant vessels are no more than dabs of the pen but so convincingly positioned that they conjure up a vast perspective.

The dark hulk of the boat gives me a sense that I'm looking into brightness beyond. There are a couple of picture-making conventions here: dark shapes against light and a balance of the bulk of the boat against the dark mass of the cloud, but it's done in such a naturalistic way that I'm sure that must be as Constable saw the scene.

There's more than a touch of Rembrandt in the drawing. It's difficult to do a seascape without thinking of Dutch painters. As in Rembrandt's drawings I feel there must be an Oriental influence here in the calligraphic pen and brush work: I like those playful curling waves in the bottom right contrasted to the back-breaking work of the men. I think of Hokusai (1760-1849), a contemporary of Constable, with his busy, often humerous, figures of fisherman and farmers about their work contrasted with the majestic curves and vortexes of nature.

There's also that strong diagonal across the composition, from upper left to bottom right, which again seems to me to have an oriental feel to it.

I

drew this second Brighton beach sketch in pen only, although Constable's

original is in pen and wash. Once again there's a squall out to sea with

birds and sailing ships giving an impression of the wind. Again there's

some evidence of everyday work in progress on the beach but there's also

a couple enjoying a bracing stroll at the edge of the sea.

I

drew this second Brighton beach sketch in pen only, although Constable's

original is in pen and wash. Once again there's a squall out to sea with

birds and sailing ships giving an impression of the wind. Again there's

some evidence of everyday work in progress on the beach but there's also

a couple enjoying a bracing stroll at the edge of the sea.

Ways of Seeing

By

the time I've sketched a couple of the Brighton beach sketches the exhibition

is filling up so, rather than hogging these little gems (there were a

couple more that I didn't sketch) I take the opportunity to sit at a bench

to sketch a detail of one of Constable's 'six-footers' as he called his

exhibition pieces, designed to cause a stir at the Royal Academy summer

show.

By

the time I've sketched a couple of the Brighton beach sketches the exhibition

is filling up so, rather than hogging these little gems (there were a

couple more that I didn't sketch) I take the opportunity to sit at a bench

to sketch a detail of one of Constable's 'six-footers' as he called his

exhibition pieces, designed to cause a stir at the Royal Academy summer

show.

Most of his landscapes include figures but his full size Sketch for Hadleigh Castle (below left, 1828-29 © Tate Gallery) is populated by a wheeling flock of birds against a turbulent sky. This reminds me of Van Gogh's Wheatfield with Crows.

In his 1972 book Ways of Seeing (which accompanied a BBC television series) John Berger shows this painting with the caption:

This is a landscape of a cornfield with birds flying out of it. Look at it for a moment.

Over the page he shows it again, with the following caption:

This is the last picture that Van Gogh painted before he killed himself

'It is hard to define exactly how the words have changed the image,' says Berger, 'but undoubtedly they have. The image now illustrates the sentence.'

Constable in Love

That's true of Constable's Hadleigh Castle. It's hard to deny, as Ann Lyles, Curator at the Tate Gallery, writes in the booklet that accompanies this exhibition, that this is:

an image of intense loneliness and decay prompted by Constable's distress following the death of his wife in 1828.

This story was explored in a recent documentary film Constable in Love. I was glad to have the opportunity to see the exhibition first, with an innocent eye, then watch the film and finally to have another opportunity to see the paintings and drawings in real life.

The television version of Constable with its energetic presenter, challenging camera angles, hand-held camera evocations of key moments in the painter's life and corrobative anecdotes from art historians and descendants of the artist is compelling in its version of events but, as Berger reminded us in Ways of Seeing:

. . . each image reproduced has become part of an argument which has little or nothing to do with the painting's original independent meaning. The words have quoted the paintings to confirm their own verbal authority.

The television version of the paintings was awesome. It conjured up an image of an energetic genius with near magical powers. Looking at the film I found myself thinking 'how could anyone, even Constable, acheive such breathtaking effects.

It's definitely worth coming back to the originals to remind yourself that he was actually working with something as simple as pigment on canvas. You could buy all the colours he used in you local art shop. When you look at the originals nothing is hidden. You can look into them for as long as you wish. You can think about them in any way you like.

Constable Clouds

As

I've said before, I like to sit and sketch, rather than just walk around

an exhibition as a way of focusing on a particular painting. This pen

and wash is from a the top corner of Hadleigh Castle. I'm sure

the longer I spent copying a painting the more I would discover in it.

As

I've said before, I like to sit and sketch, rather than just walk around

an exhibition as a way of focusing on a particular painting. This pen

and wash is from a the top corner of Hadleigh Castle. I'm sure

the longer I spent copying a painting the more I would discover in it.

Constable himself believed in making such copies. Discussing the emphasis on the work of the great masters in Royal Academy Schools of Constable's time, Mark Evans, of the V&A writes in the exhibition booklet:

Constable preferred a narrower canon of landscape painters, above all Claude, but also Rubens and Jacob Ruysdael, after whose work he produced several meticulous copies. He justified these facsimiles as 'a real property' and 'a more lasting remembrance' as opposed to a mere sketch, which would 'not serve to drink at again and again'.

I

can't get the control I want with the pen and wash so I make a couple

of quick studies of the clouds in pencil. There's something extraordinary

about Constable's storm cumulus clouds: as I draw them I get the feeling

that they are moving, in a churning motion, like real clouds. I think

the reaso for this is that if I'd been drawing from a painting of a building

or a tree I'd have particular points of reference on which to anchor my

drawing and my vision but as this is something as amorphous as a cloud

my eye has to search for the particular part of the cloud I'm drawing.

I

can't get the control I want with the pen and wash so I make a couple

of quick studies of the clouds in pencil. There's something extraordinary

about Constable's storm cumulus clouds: as I draw them I get the feeling

that they are moving, in a churning motion, like real clouds. I think

the reaso for this is that if I'd been drawing from a painting of a building

or a tree I'd have particular points of reference on which to anchor my

drawing and my vision but as this is something as amorphous as a cloud

my eye has to search for the particular part of the cloud I'm drawing.

The

kinetic quality of his clouds is a result of the depth of his understanding

of the way they behave. He said:

The

kinetic quality of his clouds is a result of the depth of his understanding

of the way they behave. He said:

We see nothing truly till we understand it

Constable clouds have the appearance of being painted in a spontaneous way. His knowledge doesn't sit heavily on his paintings.

When I sit down to make a sketch from nature, the first thing I try to do is, to forget that I have ever seen a picture

He

said that he'd learnt to see in his childhood when he became fascinated

by the visual qualities of weatherworn timbers of the bridges and locks

of the River Stour. My last sketch is of the bridge in the final version

of his six-foot canvas The Leaping Horse.

He

said that he'd learnt to see in his childhood when he became fascinated

by the visual qualities of weatherworn timbers of the bridges and locks

of the River Stour. My last sketch is of the bridge in the final version

of his six-foot canvas The Leaping Horse.

I can't resist one last quote from the artist, which could equally apply to what I try to do in my nature diary:

My limited and abstract art is to be found under every hedge and in every lane, and therefore nobody thinks it worth picking up.

![]() Next page | Previous

page | This day in 2000

| This month | Nature

Diary | Home

Page

Next page | Previous

page | This day in 2000

| This month | Nature

Diary | Home

Page

![]()