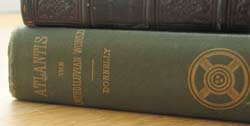

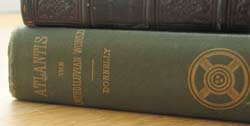

ATLANTIS:

THE ANTEDILUVIAN WORLD, by Ignatius Donnelly, published in

1882, was evidently the Da Vinci Code of its day as my copy, inscribed

as 'For my dear Mother & Sister . . . Mary Sophia Powell, Christmas

1897’ is the 24th edition.

ATLANTIS:

THE ANTEDILUVIAN WORLD, by Ignatius Donnelly, published in

1882, was evidently the Da Vinci Code of its day as my copy, inscribed

as 'For my dear Mother & Sister . . . Mary Sophia Powell, Christmas

1897’ is the 24th edition.Richard Bell's Wild West Yorkshire nature diary

Monday, 26th March, 2007

ATLANTIS:

THE ANTEDILUVIAN WORLD, by Ignatius Donnelly, published in

1882, was evidently the Da Vinci Code of its day as my copy, inscribed

as 'For my dear Mother & Sister . . . Mary Sophia Powell, Christmas

1897’ is the 24th edition.

ATLANTIS:

THE ANTEDILUVIAN WORLD, by Ignatius Donnelly, published in

1882, was evidently the Da Vinci Code of its day as my copy, inscribed

as 'For my dear Mother & Sister . . . Mary Sophia Powell, Christmas

1897’ is the 24th edition.

Even today, when we know that “Dolphin’s Ridge”, west of Madeira is the result of sea-floor spreading, the variety of evidence that Donnelly brings together is impressively varied. He brings it to life with more than 120 illustrations, mainly engravings in black and white line with just a handful in halftone.

Forty

years later this book had evidently been taken from the shelf as someone has

carefully pasted a map of the world’s “lost continents” into

the rear endpapers, cut from The Weekly Telegraph, September 7, 1935.

Forty

years later this book had evidently been taken from the shelf as someone has

carefully pasted a map of the world’s “lost continents” into

the rear endpapers, cut from The Weekly Telegraph, September 7, 1935.

Serpent

and Pillars

Serpent

and PillarsThese serpents, one from a Phœnician coin (left), the other (right) – so Donnelly says - from a coin found in Guatemala, are typical of the evidence he presents. In relation to these images he discusses the legend of the Serpent in the Garden of Eden, the Pillars of Hercules, the use of the lodestone in navigation and divination and suggests the pillars and serpent as a possible origin of the dollar mark ($).

Serpents in divination are more widespread; they appear in mythology in places as far afield as Siberia, way beyond the natural range of any snake.

I like the theory of a present-day Swiss anthropologist who notes that the

appearance of the serpent in shamanistic trance seems to have some deep physiological

basis, and suggests that this archetypal image might be somehow connected with

the double-helix structure of DNA, as if, in trance, we have the ability to

tap into the life at a cellular level.

Additions like the handwritten dedication and the newspaper cutting are amongst

the things that give books a life of their own. I can't imagine a DVD ever aquiring

that quality, as it won't be handled like a book is by it's readers over the

centuries.

Additions like the handwritten dedication and the newspaper cutting are amongst

the things that give books a life of their own. I can't imagine a DVD ever aquiring

that quality, as it won't be handled like a book is by it's readers over the

centuries.

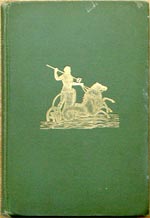

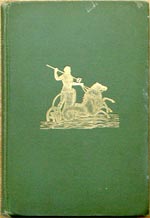

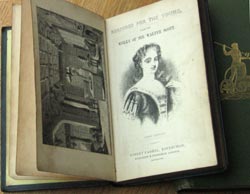

When I came across Donnelly's book in the attic I also found this leather-bound

volume of Readings for the Young, from the works of Sir Walter Scott,

published by Robert Cadell, Edinburgh, 1848. It’s nicely illustrated and,

I guess, never having read any of the Waverley Novels, a reasonable taster of

Scott’s work.

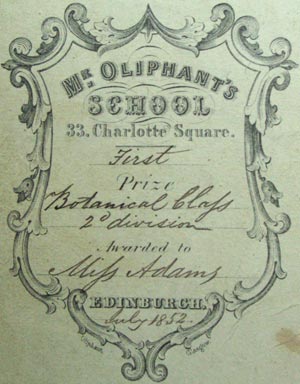

But

what fascinates me is this label on the front endpapers. Who was Mifs

Adams? I'd like to see the project that won her First Prize in the

Botanical Class, 2nd division.

But

what fascinates me is this label on the front endpapers. Who was Mifs

Adams? I'd like to see the project that won her First Prize in the

Botanical Class, 2nd division.

Thanks to Google, I was soon able to discover that Mr Oliphant was Thomas Oliphant who:

had been rector of the first “Normal School” in Edinburgh (i.e.

training school for teachers) opened by the Church in 1842. At the Disruption

he and all his staff “came out” and in 1846 he set up his own private

school, the Charlotte Square Institution for Young Ladies, at 33 Charlotte Square

. . . In 1848 the Free Church purchased Moray House in the Canongate, which

eventually became Edinburgh’s Teacher Training College and is now part

of Edinburgh University. As a Free Church elder, Thomas Oliphant attended the

General Assembly in 1869 [FCPA, vol. xxvii, 1869].

From, The Letters of William Robert Smith, (see link below)

The computer screen doesn’t show the fine detail in the engraving but you can just make out that, at the bottom, it says ‘Oliphant, Glasgow’ so there must have been a talented engraver in the family.

One of Thomas's sons (*see below), Francis Wilson Oliphant (1818-1859) was an artist and stained-glass designer who worked with Pugin in the Gothic Revival movement. A couple of months before this volume was presented as a prize, Francis married his cousin, the writer, Margaret Oliphant Wilson, in Birkenhead.

In the article on Francis, the Oliphants are described as 'an ancient but fallen family in Fife'.

Francis

Wilson Oliphant

Margaret

Oliphant in Wikipedia

Letters of William Robertson Smith includes an account of the Friday gale that hit Edinburgh in January, 1868; 'So I sallied forth and reached Mr Oliphant’s tolerable wet but safely. Princes Street was almost deserted by this time and quite covered with wreck. At one corner a baker’s hurlie had been overturned and deserted and so forth.

'I was quite alarmed to hear no news of Ellen at Mr Oliphant’s and rushed down to the Brakenridges where I was very thankful indeed to find her safe and sound, and enjoying her dinner. In fact I had the worst of it myself as I was well drenched.'

*Since I wrote this I have heard from a great, great, great nephew of Thomas Oliphant, rector of the school. He points out that Thomas was born around 1812/13, so he can't possibly be the 'Thomas Oliphant, Edinburgh' mentioned in the article as the father of Francis Wilson Oliphant who was born in 1818.

My correspondent tells me that 'the engraving in the book you mention was by Thomas's brother William who was born in Edinburgh but went to live in Glasgow'.

So is there a connection between these two Thomases who were apparently contemporaries in Edinburgh? I've heard from another member of the family who is trying to discover if they were related.

Another context in which I briefly spotted the name Oliphant was in a Timewatch

film about the last

duel fought in Scotland. In a map of the country around Kirkadly one of

the parcels of land had the name Oliphant written in the copperplate script

of the day.