Leaves and Memory

Leaves and Memory Leaves and Memory

Leaves and MemoryWild West Yorkshire, Monday 25 October 2010

previous | this month | next

SADLY we're back here in resuscitation with Barbara's mum fighting for her life again after a suspected heart attack. There's not much we can do other than keep her company and, when she complains of being too hot, fanning her with her patient file which we grabbed as we set off following the ambulance after her dawn alarm call to us.

SADLY we're back here in resuscitation with Barbara's mum fighting for her life again after a suspected heart attack. There's not much we can do other than keep her company and, when she complains of being too hot, fanning her with her patient file which we grabbed as we set off following the ambulance after her dawn alarm call to us.

But as my small art bag goes with me everywhere, I've got my sketchbook pen and watercolours with me and the handful of autumn leaves that I picked up on our brief visit to the little Faith Garden arboretum on Friday.

It's been a good year for autumn colour with many of the maples looking much yellower than the two leaves that I picked up.

Memory Boost

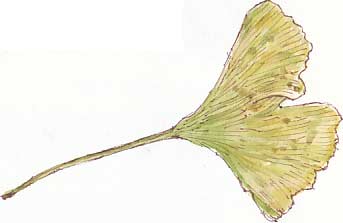

Memory BoostThe ginkgo leaves (left) deserve their place in any faith garden as it was grown by Buddhist monks in temple gardens long after it had disappeared from its natural habitat in southern China. Those parallel veins in its leaves show that it belongs to an ancient group of non-flowering plants. Fossil ginkgo leaves are found in the Jurassic rocks of the Yorkshire coast at Scarborough which date from about 150 million years ago.

Ginkgo is widely used in Chinese medicine and its uses include boosting circulation when insufficient blood is reaching the brain; for this reason it is used in treating memory loss and senile dementia.

But this hospital goes for the high tech western approach to medicine and we leave Barbara's mum in the evening settled in the cardiac ward wearing a kind of space helmet which is helping boost her oxygen levels.

Bodyscape

BodyscapeI've learnt a lot about human physiology during the last few months from the many hours that I've spent with both my mum and Barbara's mum in a variety of departments including heart, lymphatic, ear and eye. As knowledge of what is going on at a cellular level increases there's a tendency to treat the human body not as a machine - with the lungs as a pair of bellows or the inner ear as a microphone for instance - but to see it as a community of cells or even an ecosystem of sorts.

I've had the chance to catch up with the latest thinking in audiology about how the receptor cells in our inner ear cope when one section of cells is damaged; the adjoining frequencies work a little harder to make up for the gap in spectrum of audio frequencies. It would be like the violin and cello section in the orchestra trying to fill the gap if the violas didn't turn up for a concert. I guess this is a programming solution (there I go using a machine analogy) that the brain puts in place to cope with the missing frequencies. Knowing how the body and brain work out their natural solution to a problem helps fine tune the artificial aids that medicine has to offer.

As I understand it, there's now a similar view about some forms of incapacity in our breathing. When some areas of the lungs get blocked with fluids or air pockets the body shifts its attention on the remaining areas available for gaseous exchange. That makes perfect practical sense but it gives the medical teams problems when they're trying to get the previously blocked areas back in full working order again.

I realise that you can't treat the particular problems that component parts of body and brain might have in isolation; you've got to look at the whole 'landscape' and you understand that by giving minute attention to the smallest details that you're able to observe.

Richard Bell, illustrator

previous | this month | Wild West Yorkshire home page | next