Fossil Fish

Fossil Fish Fossil Fish

Fossil FishWild West Yorkshire, Wednesday 24 November 2010

previous | this month | next

THIS FOSSIL FISH is just 37mm (1.5 inches) long but it's perfect in its detail, as if it had been washed up on the strandline yesterday rather than a hundred million years ago. Actually, I don't know what period it's from as it's not one that I collected.

THIS FOSSIL FISH is just 37mm (1.5 inches) long but it's perfect in its detail, as if it had been washed up on the strandline yesterday rather than a hundred million years ago. Actually, I don't know what period it's from as it's not one that I collected.

Even with my reading glasses, I'm aware that I'm not seeing every detail so I photographed it at 10x magnification under the microscope (right).

Zooming in to 60x you can see the limestone matrix surrounding the tip of the tail of the fossil (left). The limestone itself probably consists mainly of fossil debris in the form of ground up shells, although it might also contain crystals of naturally precipitated calcium carbonate.

Zooming in to 60x you can see the limestone matrix surrounding the tip of the tail of the fossil (left). The limestone itself probably consists mainly of fossil debris in the form of ground up shells, although it might also contain crystals of naturally precipitated calcium carbonate.

Like us, fish are vertebrates and around 350-400 million years ago - not so long geologically, less than one tenth the age of our planet - our ancestors were, to judge by the fossil evidence that's available, fishlike. There's also some hint of this in the early stages that the human embryo goes through; in the fourth week of our development pharyngeal slits appear which resemble the gill slits of fish. This doesn't prove that we're related but pharyngeal arches also appear in the development of fish embryos, so that's a feature that we share with them.

Pharyngeal slits appear in the development of the embryo in all tetrapods; amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Tetrapod means 'four-legged'. Pharyngeal refers to the pharynx which in humans lies behind the mouth, nose and larynx (upper section of the windpipe) and contains the vocal chords.

Lobe-fins

Lobe-fins Tetrapods - including ourselves - are thought to be the descendants of the lobe-finned fishes of the Devonian. My drawing on the left is of Rhabdoderma tingleyense, a lobe-finned fish from the Carboniferous period that followed the Devonian. It is named after Tingley, south of Leeds, where the fossil was found in the colliery. Rhabdoderma was one of a group of lobe-finned fish that weren't ancestral to the tetrapods.

Tetrapods - including ourselves - are thought to be the descendants of the lobe-finned fishes of the Devonian. My drawing on the left is of Rhabdoderma tingleyense, a lobe-finned fish from the Carboniferous period that followed the Devonian. It is named after Tingley, south of Leeds, where the fossil was found in the colliery. Rhabdoderma was one of a group of lobe-finned fish that weren't ancestral to the tetrapods.

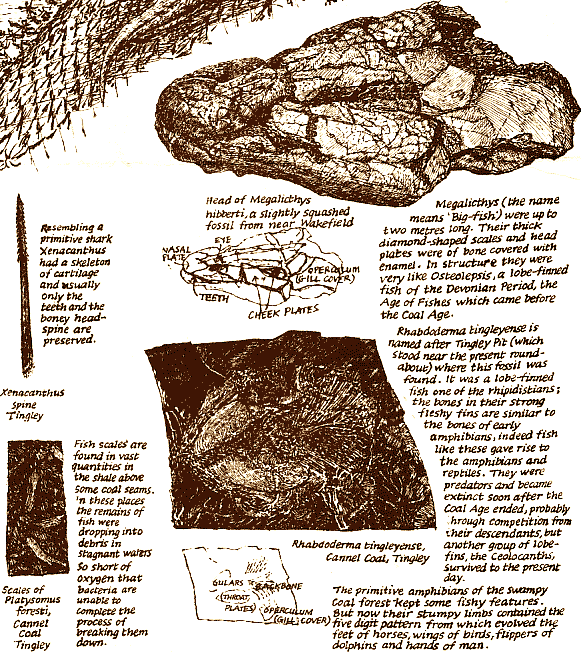

Xenacanthus (right), also from the Carboniferous period, was a primitive shark. Like all sharks it had a skeleton of cartilage so it's usually just the head-spine that gets preserved as a fossil.

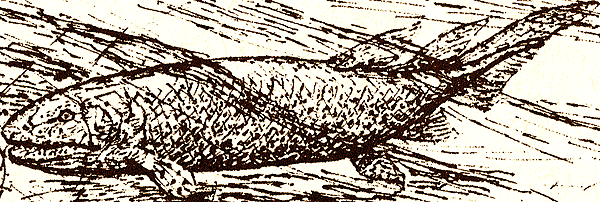

The name Megalicthys (below) means 'big-fish'. It was armoured with head plates and diamond-shaped scales. Like Rhabdoderma it was one of the lobe-finned fishes, resembling Osteolepsis, a well known lobe-fin of the Devonian.

These pen and ink drawings of Carboniferous fish, made when I was a student, were based on reconstructions in a diaorama in the fossil fish gallery of the Natural History Museum in London. Some of the key fossils found in the collieries of the West Riding of Yorkshire had found their way there. I remember a curator at Leeds Museum looking at one of my drawings of fossil fish and saying 'Ah - so that's what happened to our fossil!'.

I was taking advantage of my time in London to do some research on the fossil life of West Yorkshire for my first book published book, A Sketchbook of the Natural History of the Country Round Wakefield (1979). As you can see from the page from the book (below) I became fascinated by fossil fish and learnt the names for features like the gill cover and throat plate (operculum and gular).

When you study something in such detail it changes the way you see things. You might not think this would be true for fossil fish but on one of my long walks exploring the country around Wakefield, I made my way through the cutting of a derelict railway. I spotted an outcrop on the banking and climbed up to take a closer look. There were fossil fish scales in the black shale. I collected a few examples and took them with me next time I went drawing at the Natural History Museum. The paleontologist confirmed that they were fossil fish scales.

Richard Bell, illustrator

previous | this month | Wild West Yorkshire home page | next